An abundance of learning theories exist in education, yet no single learning theory is a magic bullet.

Learning theories presented as “new” or “innovative” often transform into academic buzzwords that spread like wildfire through educational circles. Yet, more often than not, the “innovative” idea is rooted in established learning theories or teaching methods.

Take “phenomena-based” learning.

When I meet with teachers and school administrators about Real Science-4-Kids or RATATAZ products, I am often asked if my programs are “phenomena-based.” When I first encountered this phrase, I spoke with a school principal. While the term was new to me, I indicated that everything in my chemistry program is “phenomena-based.” Chemistry itself is an observation of phenomena. It was clear that I didn’t communicate the specific meaning she was seeking – the one who checked the buzzword box – so she decided not to use our program.

This phrase, phenomena-based learning, currently dominates the educational landscape. Yet very little research is available to support the idea that phenomena-based learning is preferable to other approaches, like knowledge-based learning. Without first checking this box, I can’t move forward in a conversation about the educational benefits of Real Science-4-Kids or RATATAZ.

Phenomena-based learning is currently used as the foundation for science curricular programs in the U.S. and drives the new Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) framework. The U.S. adopted phenomena-based learning when Finland, seen as a model for educational practices, embraced phenomena-based learning in 2016. Phenomena-based learning is a derivative of project-based, problem-based, and inquiry-based learning rooted in constructivism.

I was curious about how educational buzzwords rise and fall. When did “phenomena-based learning” emerge as a popular term, and how does it compare to other educational buzzwords that have come and gone?

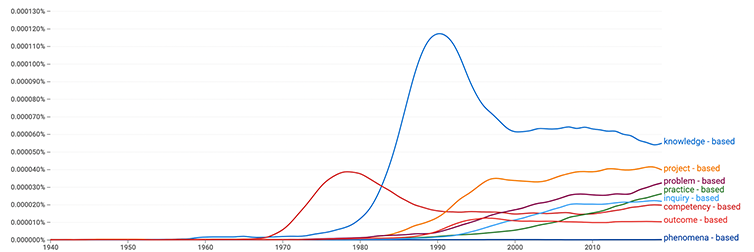

Using Google Ngram Viewer, I can track the beginning of a term’s usage, growth, and fluctuations and compare its usage to other common words or phrases. Google Ngram Viewer maps the use of words and phrases in books over any given period between 1800-and 2019. It can reflect a term’s cultural popularity over a given period.

Below is a graph of several currently and previously popular buzzwords in educational spheres.

Notice that the phrase “phenomena-based” appears as a newcomer to the crowd, with few uses in the literature compared to the more popular knowledge-based, problem-based, or project-based.

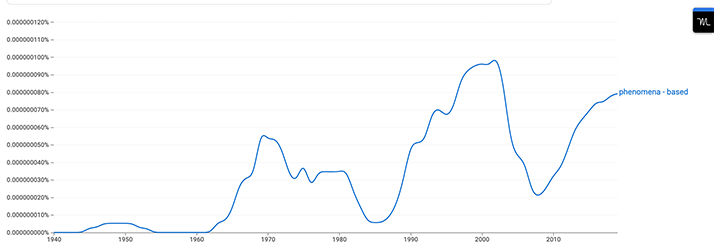

The scale is compressed for the term “phenomena-based” because it has much lower usage than the other terms. I wanted to see if there was any additional detail to this phrase, and to do this I needed to expand the scale. By isolating the term “phenomena-based” I can find the onset and fluctuations of its usage. I can see that although it hasn’t been as popular compared to other terms, it’s not new, but has come and gone before. It gained popularity in 1970, dipped by the end of the 1980s, and regained popularity in the early 2000s, dipping again before 2010 to take a turn and increase in popularity as of 2019. In other words, phenomena-based learning is not a new approach to learning, it’s just popped up as a current buzzword that feels new and exciting to educators.

Many buzzwords are floating around educational circles. Student engagement, remote-learning, higher-order thinking, Daily 5, everyday mathematics, common core aligned, critical thinking, portfolio assessment, hands-on, multiple intelligences, hybrid-learning, discovery learning, balanced reading, IEP, chunking, scientific literacy, differentiated instruction, distance-learning, direct instruction, deductive thinking, extrinsic motivation, formative assessment, inclusion, individualized instruction, inquiry-based learning, 21st-century skills, learning styles, mainstreaming, manipulative, literacy, life-long learning, flexible grouping, data-driven, SMART goals, DIBELS are all past and current educational buzzwords. I’ve even created one of my own – RATATAZ.

Buzzwords in education mainly do not harm and can offer educators a way to communicate different facets of learning to other educators. However, focusing on a single learning theory or teaching method and using buzzwords to promote a new fad is a mistake. It obscures both student and teacher needs. Educators and publishers become distracted by the shiny new object in the room and eliminate essential elements in their programs.

There are no magic bullets when it comes to improving how students learn.

Publishers should stay focused on what students need to understand complex subjects. This requires incorporating multiple learning theories into their products. At a minimum, science concepts require a hierarchical structure that includes knowledge-based and phenomena or project-based learning methods. Good teachers are well-versed in various learning methods and can meet the needs of a class or individual student by implementing theories and teaching methods to the given situation. It is crucial that curricular materials help rather than hinder a teacher’s teaching ability.